Welcome to the rapidly developing world of Long Haul Covid. With all their usual linguistic finesse, science calls it Post-Acute Sequelae of Covid-19 (PASC), or (much simpler) chronic Covid syndrome (CCS) orLong Covid Syndrome (LCS). The press and the public simply refer to this growing list of chronic aches, pains, and symptoms as Long Covid or Longhaul Covid.

This article will examine all the most common symptoms in-depth and offer advice to those who are hesitant to seek out treatment.

What exactly is LCS and how do I know if I’ve got it?

The million-dollar question. With so many varying symptoms, ranging from leg pain and breathing difficulty to brain fog and depression, healthcare is still trying to get a proper feel for the after-effects of Covid in certain individuals. Here are a few key facts you should keep in mind.

- Long Haul Covid, PASC, LCS, or CCS is a very real thing. It is now a recognized and documented medical consequence of coronavirus infection in some people. The exact percentage of people who will suffer from LCS is still unknown. This report from the CDC offers a new perspective and actual figures, but it’s too early yet to call these figures definitive and the CDC’s goal in publishing these is to draw your doctor’s attention to the incidence of LCS as becoming more commonplace.

- A study published in December of 2020, entitled Characterizing Long COVID in an International Cohort: 7 Months of Symptoms and Their Impact (links to a PDF file ) is based on survey results from more than 3,700 self-described COVID “Long Haulers” in 56 countries. They show nearly half couldn’t work full time six months after unexpectedly developing prolonged symptoms of COVID-19. A small percentage of respondents, thankfully, seemed to have bounced back from brief bouts of Long COVID, though time will tell whether they have fully recovered.

- There is no clear age group or demographic more likely to suffer from LCS. Some evidence exists to suggest that if you have pre-existing lung/heart/other conditions, these may increase your risk for developing LCS but the jury is still out on this. What is clear is that no age group is exempt from developing LCS.

- Good news. You aren’t losing your mind. This is an important point to grasp for most who start experiencing symptoms. Brain fog, depression, cognitive impairment and even waking dream states can all be caused by LCS and can have a profound impact on your mental health and thought patterns. Not seeking out help will increase your levels of stress and simply contribute to the worsening of symptoms.

- Not all medical practitioners will recognize your symptoms as LCS. Ensure your care provider is up to speed on the signs and symptoms of the condition, but don’t step into the public trap of self-diagnosis. Keep an open mind and discuss ALL your symptoms openly with your health care provider.

- What makes this condition so difficult to diagnose with certainty is that you may tick a number of boxes and not actually have LCS. Your doctor is the only person properly qualified to properly assess your condition and we’d recommend examining LCS extensively as a potential cause of any new mental health symptoms you may be experiencing, particularly if you’ve recently had a brush with the coronavirus.

- You may even have had a mild Covid infection and not been aware of it or simply passed it off as mild flu or sniffles. To play it safe, if you’re exhibiting some of the symptoms below, go in and have yourself checked out properly. A test that looks for coronavirus antibodies can help identify an earlier infection if you’re uncertain you’ve had Covid or haven’t recently had a PCR test.

So, about those symptoms. Pull up a chair, it’s a long and growing list and you can expect additional symptoms to be added to this list over the coming months and some to fall away as our understanding of the condition improves.

LCS Symptoms

In the 2020 study referenced above, the following was found among 3,762 respondents from 56 countries. We’ve used this report as the basis for this article as it encompasses the broadest set of symptoms we’ve seen described and contains more detail than other reports.

Prevalence of 205 symptoms in 10 organ systems was estimated in this cohort, with 66 symptoms traced over seven months. Respondents experienced symptoms in an average of 9.08 (95% confidence interval 9.04 to 9.13) organ systems. The most frequent symptoms reported after month 6 were: fatigue (77.7%, 74.9% to 80.3%), post-exertional malaise (72.2%, 69.3% to 75.0%), and cognitive dysfunction (55.4%, 52.4% to 58.8%). These three symptoms were also the three most commonly reported overall

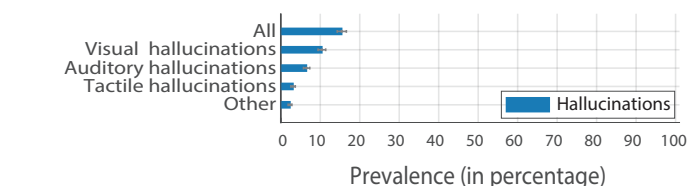

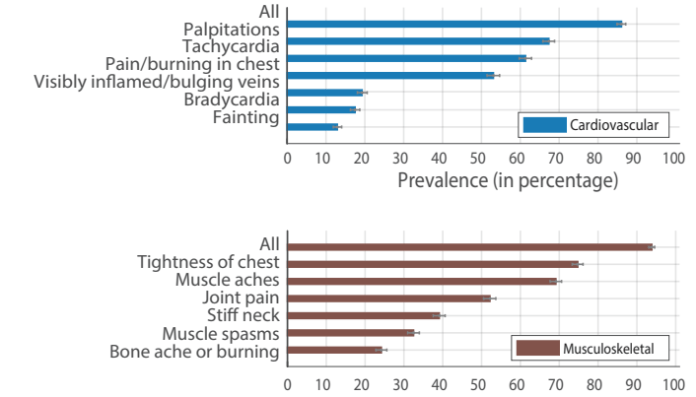

To best describe the findings in this cohort we’ve dissected the graphs published in the report and reproduced them below, as per the reports license Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). We’ll start with the neuropsychiatric symptoms (brain and mood-related). Bars represent the percentage of respondents who experienced each symptom at any point in their illness and are divided into nine sub-categories. When all rows in a given panel use the same denominator, the first row, labeled “All,” indicates the percentage of respondents who experienced any symptoms in that category. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. Base scale is prevalence (in percentage)

Nest, we’ll move on to the non-neuropsychiatric symptoms. In other words, everything to do with the rest of the body, but excluding the brain. Bars represent the percentage of respondents who experienced each symptom at any point in their illness. Symptoms are categorized by the affected organ systems. When all rows in a given panel use the same denominator, the first row, labeled “All,” indicates the percentage of respondents who experienced any symptoms in that category. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals.

As the lists of possible symptoms are lengthy, we’ve summarized them below and you can view prevalence for each in the linked report. To simplify finding your symptoms, we have again separated these as per the report and graphics above, neuropsychiatric symptoms are shown first followed by non-neuropsychiatric.

List of neuropsychiatric symptoms for LCS

Brain fog/Cognitive dysfunction and memory impairment symptoms

- poor attention or concentration (74.8%)

- difficulty thinking (64.9%)

- difficulty with executive functioning (planning, organizing, figuring out the sequence of actions, abstracting) (57.6%)

- difficulty problem-solving or decision-making (54.1%)

- slowed thoughts (49.1%)

- short-term memory loss (64.8%)

- long-term memory loss (36.12%)

- forgetting how to do routine tasks (12.0%)

- unable to make new long-term memories (7.3%)

Memory symptoms, cognitive dysfunction, and the impact of these on daily life were experienced at the same frequency across all age groups. Of those who experienced memory and/or cognitive dysfunction symptoms and had a brain MRI, 87% of the brain MRIs (n=345, of 397 who were tested) came back without abnormalities.

Speech and language symptoms

- problems with word retrieval (46.3%)

- difficulty communicating verbally (29.2%)

- difficulty reading/processing written text (24.8%)

- difficulty processing/understanding others. (23.8%)

Those who spoke two or more languages had changes to their non-primary language. Speech and language symptoms occurred in 13.0% of respondents in the first week, increasing to 40.1% experiencing these issues in month 4. 38.0%of respondents with symptoms for over 6 months reported speech and language symptoms in month 7.

Sensorimotor symptoms

- numbness

- coldness in a body part

- tingling/pins and needles

- electric zap

- facial paralysis

- facial pressure/numbness, and weakness

Tingling, prickling, and/or pins and needles were the most common at 49% of respondents. Refer to Supplemental Table S3 (shown below) for the most commonly affected anatomical locations.

Sleep-related symptoms

78.6% of respondents experienced difficulty with sleep. The table below lists each type of sleep symptom, as well as the percentage of respondents with that symptom who also listed it as pre-existing (before COVID-19 infection).

Headaches

Headaches were reported by 77.0% of participants, with the most common manifestations being ocular 40.9%, diffuse 35.0%, and temporal 34.0%. 24.0% of respondents reported headaches after thinking/mental exertion and 23.0% experienced migraines. Of those experiencing migraines, 56.4% did not list migraines as a pre-existing condition. 46% of all respondents reported headaches during week 1, 54% of respondents experiencing symptoms in month 4 reported headaches in month 4, and 50% of respondents experiencing symptoms in month 7/reported headaches in month 7.

Emotion and mood

- Anxiety (the most common psychological symptom reported at 57.9%)

- Irritability (51.0%)

- Depression (47.3%)

- Apathy (39.2%)

- Mood lability, assessed by “mood swings” and “difficulty controlling emotions (46%)

- Suicidality (11.6%)

- Mania and hypomania (2,6 AND 3.4% respectively)

Of those who reported anxiety, 61.4% had no anxiety disorder prior to COVID. Of those who reported depression, 55.0% had no depressive disorder prior to COVID.

Taste and smell

- Loss of smell ((35.9%)

- Loss of taste (33.7%)

- Altered sense of taste (25.1%)

- Phantom smells (i.e. olfactory hallucinations or phantosmia) (23.2%)

- Altered sense of smell (19.8%)

Phantom smells were accompanied by a write-in question asking for a description of the smells, in which the most common words were “smoke,” “burning,” “cigarette,” and “meat.” Changes to smell and taste were more likely to occur earlier in the illness course, with 33.2% occurring in week 1. 25.2% of respondents with symptoms for over 6 months experienced changes to taste and smell in month 7.

Hallucinations

The most common hallucination reported was olfactory hallucinations 23.2%, mentioned above. Visual hallucinations were reported by 10.4% of respondents, auditory hallucinations by 6.5%, and tactile hallucinations by 3.1%.

List of non-neuropsychiatric symptoms for LCS

Systemic

- Fatigue (98.3%)

- Weakness (44.5%

- Elevated temperature below 100.4F (58.2%)

- Fever above 100.4F (30.8%)

3.0% (113 respondents) experienced a continuous fever (>100.4F) for 3 or more months, and 15.0% (563 respondents) experienced an elevated temperature, continuously, for 3 or more months. Skin sensations of burning, itching, or tingling without a rash were reported by 47.8% of respondents.

Reproductive/Genitourinary/Endocrine

- Menstrual/period issues (36.1% of respondents with active menstrual cycle)

- Abnormally irregular periods (26.1%,)

- Abnormally heavy periods/clotting (19.7%)

- Post-menopausal bleeding/spotting among cis females over 49 (4.5%)

- Early menopause among cis females in their 40s (3.0%)

- Extreme thirst (35.8%)

- Bladder control (14.1%)

Sexual dysfunction occurred across genders, experienced by 14.6% of male respondents, 8.0% of female respondents, and 15.9% of nonbinary respondents. 10.9% of cis male participants and 3.2% of nonbinary participants reported pain in testicles.

Cardiovascular (heart and circulation)

- Heart palpitations (67.4%)

- Tachycardia (61.4%)

- Pain/burning in the chest (53.1%)

- Fainting (12.9%)

Cardiovascular symptoms were more common over the first 2 months than in later months. Even so, 40.1% of respondents with symptoms for over 6 months experienced heart palpitations, 33.7% experienced tachycardia, and 23.7% experienced pain/burning in the chest in month 7.

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)

To screen for POTS, participants were asked whether they had the ability to measure their heart rate, if their heart rate changed based upon posture, and if standing resulted in an increase of over 30 BPM. Of the 2,308 patients who reported tachycardia, 72.8% (1680) reported being able to measure their heart rate. Of those, 52.4% (570) reported an increase in heart rate of at least 30 BPM on standing.

Musculoskeletal

- Chest tightness (74.8%)

- Muscle aches (69.1%)

- Joint pain (52.2%)

Musculoskeletal symptoms were common in this cohort, seen in 93.9%. In month 7, chest tightness affected 32.9% of month 7 respondents and muscle aches affected 43.7% of month 7 respondents

Immunologic and Autoimmune

- Heightened reaction to old allergies (12.1%)

- New allergies (9.3%)

- New or unexpected anaphylaxis reactions were notable at 4.1%

20.3% of respondents (n=765) reported experiencing changes in sensitivity to medications,

Reactivation and test results for latent disease

Since being infected with SARS-CoV-2, 2.8% of respondents reported experiencing shingles (varicella-zoster reactivation), 6.9% reported current/recent EBV infection, 1.7% reported current/recent Lyme infection, and 1.4% reported current/recent CMV infection. Detailed results are shown in the table below.

HEENT (Head, ears, eyes, nose, throat)

28 symptoms were defined as symptoms of the head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat (graphic above). All respondents experienced at least one HEENT symptom. A sore throat was the most prevalent symptom (59.5%) which was reported almost twice as often as the next most prevalent symptom, blurred vision (35.7%). Within this category, symptoms involving vision were as common as other organs. Notably, 1.0% of participants reported a total loss of vision (no data on the extension and duration of vision loss were collected).

Ear and hearing issues (including hearing loss), other eye issues, and tinnitus (ringing in the ears) became more common over the duration studied. Tinnitus, for example, increased from 11.5% of all respondents reporting it in week 1 to 26.2% of respondents with symptoms for over 6 months reporting it in month 7.

Pulmonary and Respiratory (lungs)

- Shortness of breath (77.4%)

- Dry cough at (66.2%)

- Breathing difficulty with normal oxygen levels (60.4%)

- Rattling of breath (17.0%)

Dry cough was reported by half of the respondents in week 1 (50.6%) and week 2 (50.0%) and decreased to 20.1% of respondents with symptoms for over 6 months in month 7. Shortness of breath and breathing difficulties with normal oxygen increased from week 1 to week 2 and had a relatively slow decline after month 2. Shortness of breath remained prevalent in 37.9% of respondents with symptoms in month 7.

Gastrointestinal (stomach)

- Diarrhea (59.7%)

- Loss of appetite (51.6%)

- Nausea (47.8%,)

Of respondents experiencing symptoms after month 6, 20.5% reported diarrhea and 13.7% reported a loss of appetite in month 7.

Dermatologic (skin)

- Itchy skin (31.2%)

- Skin rashes (27.8%)

- Petechiae (17.8%

- COVID toe (13.0%)

COVID toe, petechiae, and skin rashes were most likely to be reported in months 2 through 4 and decreased thereafter.

Post-exertional malaise

The survey asked participants whether they have experienced “worsening or relapse of symptoms after physical or mental activity during COVID-19 recovery”. Borrowing from Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) terminology, this is referred to as postexertional malaise (PEM). 89.1% of participants reported experiencing either physical or mental PEM.

- Of the respondents who experience PEM triggered by physical exertion, 49.6% experience it the following day, 42.5% experience it the same day, and 28.7% experience PEM immediately after.

- Of the respondents who experience PEM triggered by mental exertion, 42.2% experience it the same day, and 31.4% experience it immediately after.

For some respondents the time PEM started varied. A high number of the respondents with PEM (68.3%) indicated that the PEM lasted for a few days. For physical exertion, the mean severity rating was 7.71, and for mental exertion, the mean severity rating was 5.47.

Recovery and long term prognosis for LCS

Now you know the possible effects of LCS the next question on everyone’s mind is an obvious one. Is this permanent or do people recover, and if they do, what sort of time frames are we looking at.

These are both difficult questions, particularly as we are still only getting to grips with the condition and we don’t have a long enough frame of reference yet to answer the question definitively. Obviously, the degree to which your organs have been affected, pre-existing conditions, and the type of symptoms you exhibit all play a role. Let’s look again at the cohort from the report above.

Relapses: triggers & experience

Patients with Long COVID can experience relapsing-remitting symptoms. A minimum of 85.9% of respondents reported experiencing relapses. Respondents characterized their relapses as occurring in an irregular pattern (52.8%) and in response to a specific trigger (52.4%). The most common triggers of relapses, or of general worsening of symptoms, that respondents reported were

- Physical activity (70.7%)

- Stress (58.9%)

- Exercise (54.39%)

- Mental activity (46.2%

- More than a third of menstruating participants experienced relapses during (34.3%) or before menstruation (35.2%).

Heat and alcohol were other triggers of relapse. Triggers that were written in by respondents included food with sugar and high histamines (reported by 70 respondents); lack of sleep or rest (64 respondents); cold air (39 respondents); overworking or schoolwork (28 respondents); smoke, pollution, and chemical odors (24 respondents).

Approximately half (51.7%) of respondents indicated that their symptoms have slowly improved over time, while 8.9% indicated that their symptoms have gradually worsened and 10.8% have had symptoms rapidly worsen over time.

Remaining symptoms after 6 months

Only 164 out of 3762 participants (4.4%) experienced a temporary break in symptoms. The remaining participants reported symptoms continuously, until symptom resolution or up to taking the survey. A total of 2454 (65.2%) respondents were experiencing symptoms for at least 6 months. For this population, the top remaining symptoms after 6 months were primarily a combination of systemic and neurological symptoms. Over 50% experienced the following symptoms:

- Fatigue (80.0%)

- Post-exertional malaise (73.3%)

- Cognitive dysfunction (58.4%)

- Sensorimotor symptoms (55.7%)

- Headaches (53.6%)

- Memory issues (51.0%)

In addition, between 30%-50% of respondents were experiencing the following symptoms after 6 months of symptoms:

- insomnia

- heart palpitations

- muscle aches

- shortness of breath

- dizziness and balance issues

- sleep and language issues

- joint pain

- tachycardia

- other sleep issues.

How is LCS affected by pre-existing conditions?

Again, let’s examine the data from the cohort. Most patients (83%) reported at least one pre-existing condition. The most commonly reported pre-existing conditions were;

- Seasonal allergies (36.3%)

- Environmental allergies (24.1%)

- Migraines (18.7%)

- Asthma (17.1%)

Other conditions of note include acid reflux (12.2%), irritable bowel syndrome (12.9%), vitamin D deficiency (11.8%), obesity (10.7%), hypertension (9.1%), hyperlipidemia (7.4%), and myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (2.5%).

In the United States, the prevalence of asthma in the general population is 7.7%. While this cohort is not representative of the U.S. population, the prevalence of asthma (17.07%) should be noted.

Making it personal, the voices of respondents

We’ve added these, not to concern you, but to allow you a deeper understanding of the extent to which LCS can affect your life and if you’re experiencing these symptoms, to assure you, you not losing your mind. We strongly urge you to seek help from a trusted medical practitioner who is knowledgeable in the field of LCS.

On Cognitive Dysfunction and Memory Loss

“mother has started to help me take the medications I’m on because I can’t remember if I’ve taken them immediately after having the bottle in my hand”

“was trying to fill out a mortgage application form and couldn’t remember our rent. I put £3750 a month. My partner said, no it’s £1375. So I put £13750. My partner said no, so I tried several more times — I was just guessing numbers”

“sitting on the toilet to pee and had to stop for a second to think if I was really there and not about to pee myself or the bed”

“don’t remember what I did in March or April up until the last week of April. I had almost nothing on my schedule. I don’t know what I did”

“put food on the gas stove and walked away for over an hour, only noticing when they were smoking/burning”

“forget how to do normal routines like running a meeting at work”

“felt lost driving and had to stop and find my position in a GPS to be able to drive back home. It’s a route I have done hundreds of times”

“have trouble comprehending new ideas”

“can’t hold multiple trains of thought […] If I tell myself I have to water my plants, I must do it before another thought comes into my mind because otherwise, I will forget”

“can’t follow plots in movies or tv shows, have to write everything down, have to remember to look at notes”

“had to terminate many phone calls because I could no longer comprehend the speakers nor communicate clearly with them”

“used to do the New York Times crossword puzzle every single day and I can’t even manage the mini ones now”

“can’t focus on reading complex texts, and it makes me feel very tired to do that”

“Found that I had become dyslexic — and knew it was happening at the time, could not remember how to spell words — also found I was missing words from sentences and sometimes writing things that did not make sense”

Should I see a psychiatrist or psychologist first?

Medika’s advice on this is no. Your first port of call should be a doctor qualified to recognize the symptoms of LCS. The right provider can assist you with an appropriate treatment strategy without necessarily resorting to psychotropic drugs and antidepressants which can have serious long-term implications for your mental health.

First, explore the probable diagnosis of LCS with a qualified medical practitioner, particularly if you’re experiencing a number of the symptoms listed above.

If you would like to share your personal experiences of LCS, we encourage you to use the form below and we’ll add your voice to the conversation.